TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Symptoms and Prevalence of PMS

2. Potential Hormone Fluctuations Seen in PMS

3. Underlying Contributors to PMS

- 3.1. Stress

- 3.2. Blood Sugar Regulation

- 3.3. Gut Health

5. Nutrition and Lifestyle Support for PMS‡

- 5.1. Diet

- 5.2. Exercise

- 5.3. Stress

7. Pure Encapsulations® Nutrient Solutions

SYMPTOMS AND PREVALENCE OF PMS

The menstrual cycle reflects a woman’s overall health status and has been considered her fifth vital sign.1 For some women, their menstrual cycle is a dreaded time of the month, bringing with it a cyclic pattern of pain and discomfort that impacts their daily life.

In fact, approximately 90% of cycling females report that they experience at least one mood related or physical symptom in the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle.2

When a woman experiences one or more symptoms in the five days prior to the onset of her menses, this is known as PMS, or premenstrual syndrome.3

Up to 30% of reproductive-age women experience PMS and report a number of emotional and physical symptoms:3

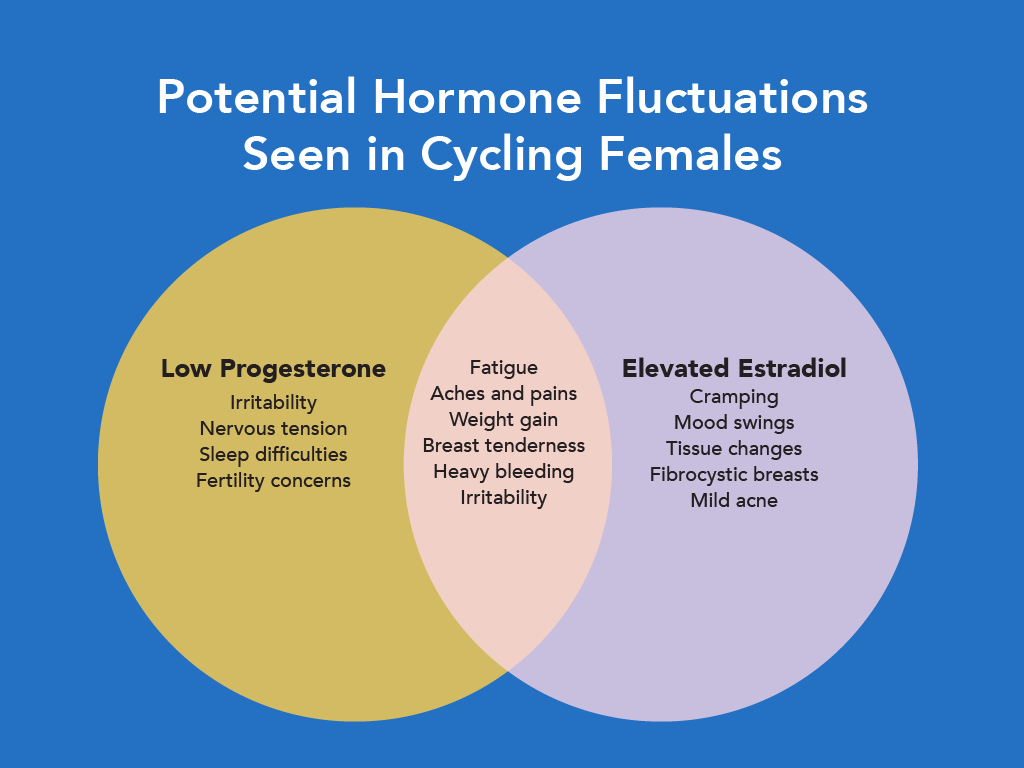

POTENTIAL HORMONE FLUCTUATIONS SEEN IN PMS

While the cause of PMS is multifactoral, the fluctuation of estrogen and progesterone levels during the menstrual cycle play a role. In some individuals, excess or depletion of these hormones can contribute to symptoms.

Since progesterone is required to balance estrogen’s activity, elevated estradiol should be viewed relative to progesterone levels. The natural fluctuation of estrogen can contribute to PMS symptoms and can occur when:4

- Progesterone is low

- Both estrogen and progesterone are in normal ranges, but estrogen is higher than progesterone

- Phase I detoxification metabolites are elevated

- Estrogen is elevated outside the luteal phase

While hormonal fluctuations can be a contributing factor to PMS symptoms, research suggests that in some women PMS may be caused by a heightened sensitivity to the normal rise and fall of estrogen and progesterone during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, impacting the serotonergic and GABAergic systems.2, 5

UNDERLYING CONTRIBUTORS TO PMS

Owing to the complex interactions between the hormones, body tissues, cells and the gut microbiome that coordinate the menstrual cycle, a practitioner may be uncertain which system to address first in patients with PMS. While there are many approaches, there are three underlying contributors and strategies that can help move the needle in caring for patients with PMS: stress, blood sugar regulation and gut health.

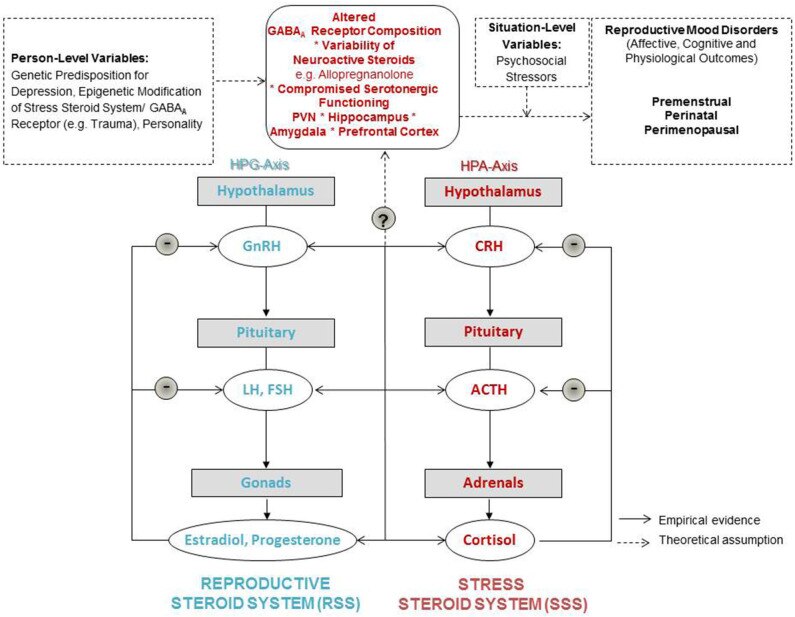

STRESS

High stress is a contributing factor to PMS symptoms, as a bidirectional relationship exists between the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

The paraventricular nucleus in the brain, which contains several neurons that regulate the HPG axis and expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), also contains neurons which regulate the HPA axis and expression of corticotropin-releasing-factor (CRF).6 This area of the brain is also ubiquitous with GABAergic and serotonergic neurons. The neural overlap of these regulating systems is one contributing factor to their interactions, as both the HPG and HPA axes are vulnerable to hormones produced by the other.6, 7

In animal studies, various stress models and exogenous cortisol have been shown to suppress GnRH and luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion.6 Corticotropin-Releasing Factor, released in response to stress, can increase aromatase production in the brain and promote increased estrogen levels.8 Conversely, progesterone and its metabolite, allopregnanolone, are able to modulate HPA axis function due to their interaction with GABAergic neurons.6 Estradiol can positively and negatively impact HPA axis reactivity, hypothesized to be due to the distribution of both Erα and ERβ receptors in the parts of the brain responsible for HPA axis regulation.6, 7

Credit: Schweizer-Schubert S et al. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Jan 18;7:479646. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.479646. PMID: 33585496; PMCID: PMC7873927.

A controlled study conducted by Hou et al. attempted to determine basal HPA axis activity in women with PMS by measuring salivary cortisol levels mid-follicular and mid-luteal phase. Compared to healthy controls, women with PMS exhibited an attenuated cortisol awakening response, a potential indicator for HPA axis dysregulation when combined with markers of HPA axis function and other factors.9, 10 These findings align with previous experiments in women with premenstrual symptoms that found hypoactivity of the HPA axis in response to stress.11, 12

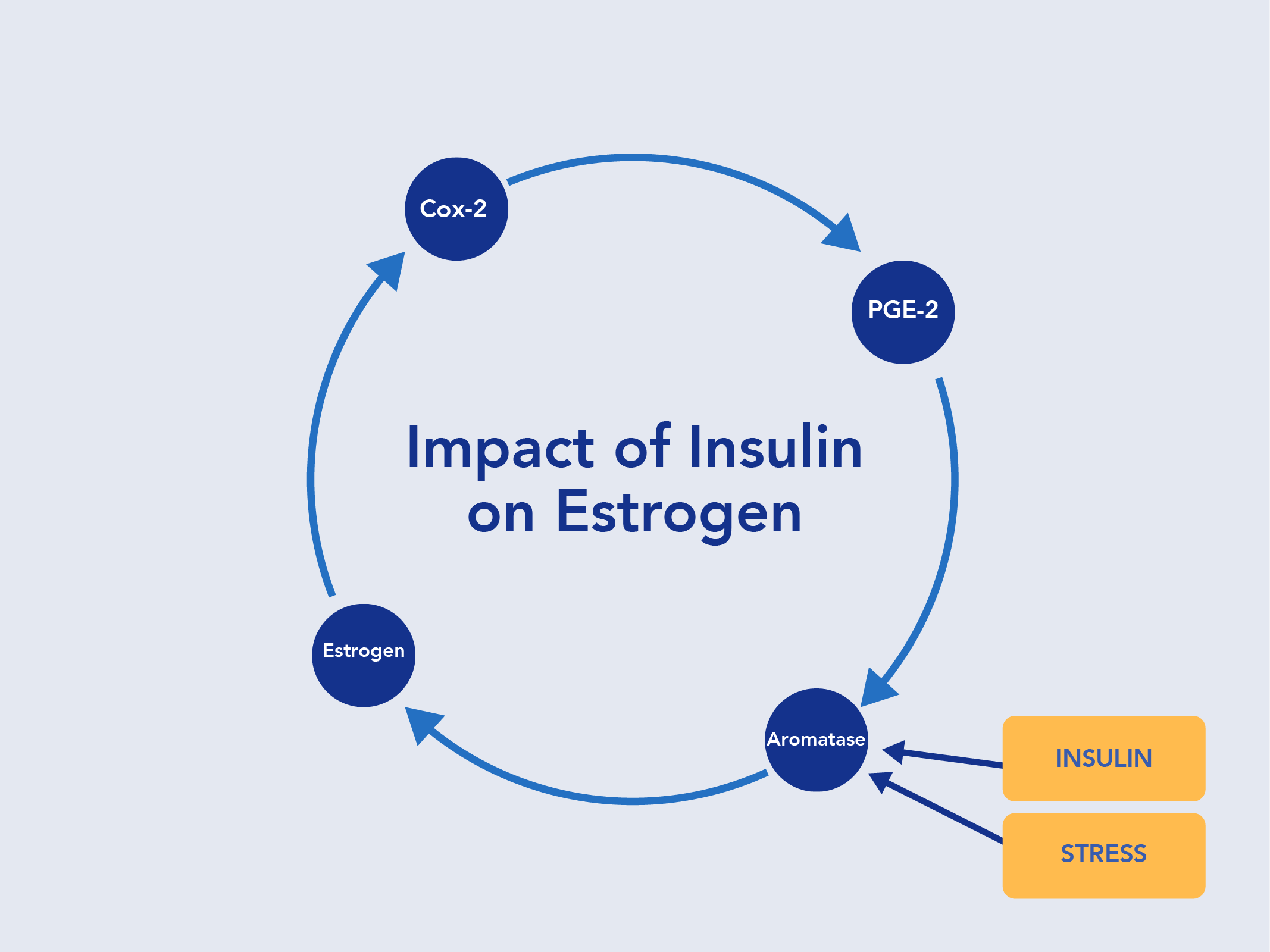

BLOOD SUGAR REGULATION

Fluctuations with glucose metabolism may occur during the luteal phase in some women with PMS. Decreased tissue sensitivity to insulin and a worsening of glycemic control in the luteal phase have been reported in women with higher estradiol or progesterone levels, compared to the follicular phase.13, 14, 15, 16

Higher circulating levels of insulin can impact production of Sex Hormone Binding Globulin, or SHBG, and can elevate estrogen production by increasing aromatase.17 A transport protein, SHBG binds to sex hormones like estrogen and testosterone and regulates their bioavailability. When SHBG production is decreased, more hormones are available in their active form to reach target tissues and cause symptoms. In addition, low plasma SHBG can be an early indicator of insulin resistance.18

GUT HEALTH

In a survey examining premenstrual emotional and GI symptoms in 156 healthy women, over 70% of the women surveyed listed one or more GI symptom in the five days prior to their menses, including pain, bloating and altered bowel habits—typically in the form of occasional diarrhea.19

Fluctuations in prostaglandins and hormones throughout the menstrual cycle can impact numerous functions of the gut, including motility, pain sensitivity and immune function, contributing to the common GI symptoms seen in PMS.

Sex hormones in the gut also communicate with neurotransmitters involved in signaling along the gut-brain axis, often leading to co-existing emotional and GI symptoms in women with PMS.18

The gut microbiome plays a critical role in the regulation of estrogen metabolism. Microbes in the gut encode enzymes responsible for the biotransformation of estrogen and its elimination through the stool. Altered gut microbiota can increase activity of β- glucuronidase enzymes that engage in deconjugation of estrogens and restore their biological activity.20 Reactivated estrogens can then be reabsorbed into the bloodstream where they are free to reach target tissues.

The relationship between the gut microbiota and estrogen is bidirectional, however; estrogen levels can influence the composition and diversity of the gut microbiota, and reduced diversity of gut microbiota can affect estrogen levels.19

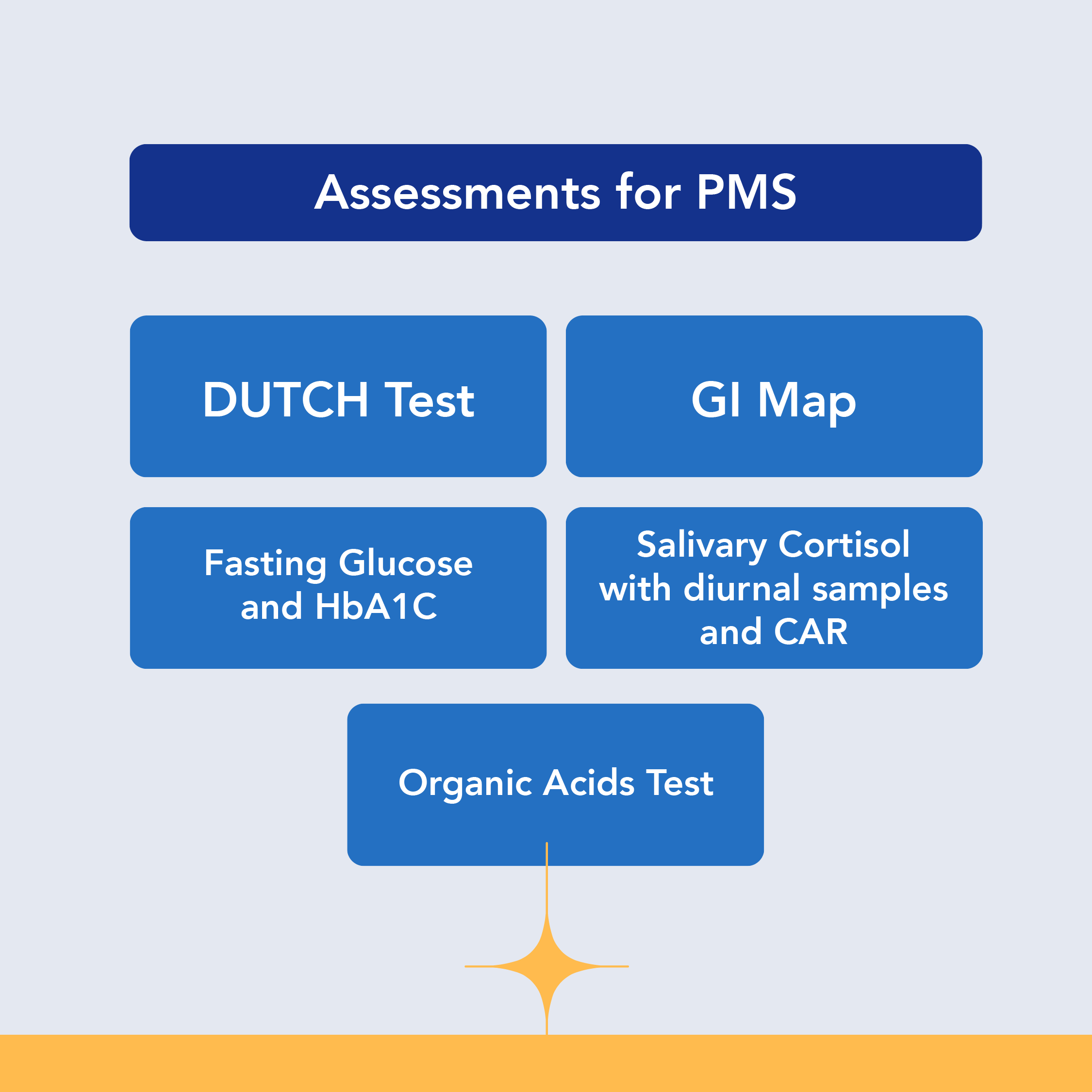

ASSESSMENTS FOR PMS

Assessments for PMS should explore hormone levels during the luteal phase, gut health, blood sugar regulation, HPA axis function, nutrient status and neurotransmitter function.

NUTRITION AND LIFESTYLE SUPPORT FOR PMS

Nutrition and lifestyle play crucial roles in managing PMS because they can influence hormonal balance, energy, mood and overall well-being. Making positive changes in diet, stress management and physical activity may help alleviate the severity of PMS symptoms for many individuals.

DIET

Diet plays a significant role in moving the needle for individuals with PMS.

Cross-sectional studies have identified that most women experience food cravings during their luteal cycle, particularly for high-calorie, high-sugar, high-fat, and high-salt foods, and that severity of PMS symptoms is positively correlated with intake of these types of foods.21, 22

Due to the influence of insulin, stress, and the gut microbiome on menstrual health, a phytonutrient-rich, preferably organic, whole foods diet should be emphasized for women with PMS. The Mediterranean diet, comprised of a high intake of fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts and olive oil can be beneficial for women with PMS.

A 2022 cross-sectional study examined dietary patterns and PMS symptoms in 262 women ages 20-49. A lower prevalence of PMS was found in women who adhered to a Mediterranean diet, and a higher prevalence of PMS was found in women who had low adherence to a Mediterranean diet and higher intake of snacks and breads.23 The consumption of sugar has also been significantly associated with an increase in nervous tension symptoms in PMS.24

Encouraging fermented foods and adequate fiber can support motility, stool consistency, and balance in the patient’s gut microbiome, as well as support the excretion of excess estrogen.

EXERCISE

Regular physical activity can have a positive effect on both emotional and physical PMS symptoms. Exercise increases endorphins, helps regulate cortisol and ovarian hormone levels, and can reduce prostaglandin levels.2, 25 A randomized, controlled trial examined the effects of 20 minutes of aerobic exercise three times a week on PMS symptoms in 65 women and found that the intervention group experienced a significant reduction in headaches, nausea, bowel changes and appetite changes after 8 weeks, compared to controls.26 In a systematic review of 17 randomized and nonrandomized studies that included over 8,800 women, regular exercise was shown to reduce nervous tension, anger, general pain and occasional constipation symptoms.27 Forms of exercise included strength training, yoga, Pilates and aerobic exercise. While many studies have demonstrated significant improvement in PMS symptoms after 8 weeks, some women may experience a benefit after just one menstrual cycle, especially if they are new to exercising.28

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists endorses routine exercise to help manage physical and affective premenstrual symptoms and highlights yoga as a beneficial option to reduce overall PMS symptoms.2

STRESS

In a 2022 meta-analysis of 77 studies that examined factors associated with prevalence and severity of menstrual-related symptoms, stress was determined to be significantly associated with prevalence of PMS.24 Stress in a patient raises cortisol, impacts glycemic control and insulin sensitivity and increases prostaglandins.24, 29

There are numerous recommendations the practitioner can make for a patient needing to manage stress, including relaxation techniques, aerobic exercise, meditation and yoga. Interestingly, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) has been the most studied psychosocial practice for addressing PMS symptoms and is endorsed by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecologists as a recommended option. CBT has been shown to provide statistically significant reductions in symptom scores compared to controls in nervous tension, low mood, negative behavioral changes, symptom intensity and interference with daily life.21

NUTRIENT SUPPORT

Along with dietary and lifestyle changes, nutrients that support blood sugar balance, emotional well-being, GI health and healthy prostaglandin and eicosanoid levels can help improve patient outcomes.30, 31, 32, 33, 34

Vitamin B6 has a positive effect on premenstrual mood and may enhance the effect of magnesium.30‡

Healthy intracellular magnesium levels have been associated with maintaining positive mood during the luteal phase.31 Magnesium also plays an important role in nervous system sensitivity, providing support for muscle comfort, breast comfort and emotional well-being associated with the menstrual cycle.32

Calcium promotes healthy smooth muscle function and menstrual comfort.33

Vitamin D supports healthy smooth muscle function and menstrual comfort, due to its ability to promote healthy calcium levels, cyclic hormone function and neurotransmitter activity.34‡

Omega-3 Fatty Acids moderate prostaglandin and leukotriene production, supporting healthy connective tissue.35 Research suggests that omega-3 fatty acids may also play a role in maintaining gastrointestinal cell health by supporting healthy eicosanoid production.‡

Eleuthero is a highly recognized adaptogen thatpromotes physiological balance and moderatesoccasional stress. In part, it helps moderate the production of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) and corticosterone activity.36‡

Rhodiola supports energy and mental function.37

Chaste tree/Vitex has been traditionally used and clinically studied for the beneficial support it provides to the hypothalamus and pituitary.38‡

l-Theanine may be helpful for premenstrual support and promote alpha wave production in the brain, an indication of relaxation.39, 40‡

PURE ENCAPSULATIONS® NUTRIENT SOLUTIONS

Pure Encapsulations provides products designed to complement your supplement plans for patients who need overall support. We offer nutrients individually and in combination to meet all your patient’s unique needs when it comes to supporting healthy stress response, moderating food cravings, encouraging healthy mood, and promoting healthy GI and cyclic hormone function. Pure Encapsulations can help you move the needle toward your patient’s overall menstrual comfort.‡

PMS Essentials supports the health and activity of the adrenal glands and promotes physiological balance and moderates occasional emotional stress. It also promotes optimal energy reserves and healthy immune function.‡

O.N.E.TM Multivitamin supports overall wellness with vitamins, minerals and antioxidants.‡

O.N.E.TM Omega promotes joint and connective tissue integrity and cardiovascular health.‡

Magnesium (glycinate) encourages healthy cognitive and neuromuscular function and helps with calcium metabolism and bone mineralization.‡

l-Theanine promotes relaxation without causing drowsiness and offers premenstrual support, including supporting a healthy mood.‡

CarbCrave Complex moderates carbohydrate intake and helps lessen appetite by supporting neurotransmitter function.‡

Phyto-ADR supports adrenal gland health and promotes physiological balance and moderates occasional emotional stress. Supports optimal energy reserves and promotes immune function. May help to moderate mild fatigue under stressful conditions.‡

Best-Rest Formula provides support for occasional sleeplessness, encourages the onset of sleep as well as healthy sleep quality and supports natural relaxation of the nervous system.‡

PureGG 25B is our highly researched Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supplement that supports immune, G.I. and overall health across all ages. Our PureGG 25B is a human origin strain, selected for its resistance to gastric acidity, adhesion properties and ability to support healthy gut microflora.‡

Pure Encapsulations only uses premium ingredients backed by verifiable science, so you can be confident you are recommending products with quality, purity, and potency.

SUMMARY

There is moderate evidence that supports the use of pharmaceuticals like SSRIs for the treatment of PMS symptoms. The rate of relapse is high in patients that stop SSRIs and most patients need to maintain use of them until menopause.2

Certain medications, such as SSRIs, may be appropriate and should be used under the recommendation of your healthcare professional for managing chronic, long-term, and/or more serious symptoms related to PMS. Dietary supplements are not intended to replace the use of such medications.

However, if looking for a way to potentially manage common PMS symptoms, the supplement recommendations mentioned may be appropriate, along with other dietary and lifestyle changes.

The practitioner who can provide support and lifestyle recommendations that address the root causes of patient specific PMS symptoms can provide care that makes a difference for female patients, while also improving their overall health.

RESOURCES

PMS Protocol:‡ This protocol offers focused interventions to support menstrual comfort in patients with premenstrual syndrome.‡

Nutrient Solutions to Complement the 5R Protocol: This blog post covers nutrient solutions that supplement the 5R Protocol and addresses factors related to leaky gut and other GI concerns.

Drug-Nutrient Interactions Checker: Offers scientifically supported, clinically relevant information that’s easy to understand with product suggestions based on verifiable science.

You can also explore Pure Encapsulations® to find On-Demand Learning, Clinical Protocols, and other resources developed with our medical and scientific advisors.

REFERENCES

- NIH. Accessed on February 20, 2024.

- Clinical Practice Guidelines. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dec 2023. Accessed on February 20, 2024.

- Trout KK, Teff KL. Curr Diab Rep. 2004 Aug;4(4):273-80. doi: 10.1007/s11892-004-0079-4. PMID: 15265470.

- Dutch Interpretive Guide. Precision Analytical. 2023: 45-51.

- Schweizer-Schubert S, Front Med (Lausanne).Jan 18 2021.18(7):479646. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.479646.

- Handa R and Weiser M. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2014 April ; 35(2): 197–220. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.11.001.

- Acevedo-Rodriguez A et al. J Neuroendocrinol. 2018 Oct;30(10):e12590. doi: 10.1111/jne.12590. Epub 2018 Aug 7.

- Dickens MJ et al. J Neuroendocrinol. 2013 Apr;25(4):329-39. doi: 10.1111/jne.12012.

- Hou L et al. Stress, 22:6, 640-646, DOI:10.1080/10253890.2019.1608943

- Stadler T et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016; 63: 414-432

- Huang et al. Stress. 2015. 18(2):160-168. DOI: 10.3109/10253890.2014.999234

- Klatzkin RR et al. J Psychosom Res. 2014 Jan;76(1):46-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.11.002. Epub 2013 Nov 12. PMID: 24360141; PMCID: PMC3951307.

- Escalante Pulido JM et al. Arch Med Res. 1999 Jan-Feb;30(1):19-22. doi: 10.1016/s0188-0128(98)00008-6. Erratum in: Arch Med Res 1999 May-Jun;30(3):265. PMID: 10071420.

- Yeung EH et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Dec;95(12):5435-42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0702. Epub 2010 Sep 15. PMID: 20843950; PMCID: PMC2999972.

- Valdes CT et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991 Mar;72(3):642-6. doi: 10.1210/jcem-72-3-642. PMID: 1997519.

- Zarei S et al. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2013 Jun;40(2):76-82. doi: 10.5653/cerm.2013.40.2.76. Epub 2013 Jun 30. Erratum in: Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2013 Sep;40(3):141. PMID: 23875163; PMCID: PMC3714432

- Daka B et al. Endocr Connect. 2012 Nov 19;2(1):18-22. doi: 10.1530/EC-12-0057. PMID: 23781314; PMCID: PMC3680959.

- Chen C et al. Minerva Endocrinol. 2010 Dec;35(4):271-80. PMID: 21178921; PMCID: PMC3683392.

- Bernstein MT et al. BMC Womens Health. 2014 Jan 22;14:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-14-14. PMID: 24450290; PMCID: PMC3901893.

- Hu S. et al. Gut Microbes. 2023 Jan-Dec;15(1):2236749. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2236749. PMID: 37559394; PMCID: PMC10416750.

- Meneghesso et al. Int J Nutrology. 2022. doi.org/10.54448/ijn2236

- Hashim MS et al. Nutrients. 2019 Aug 17;11(8):1939. doi: 10.3390/nu11081939. PMID: 31426498; PMCID: PMC6723319.

- Kwon YJ et al. Nutrients. 2022 Jun 14;14(12):2460. doi: 10.3390/nu14122460. PMID: 35745189; PMCID: PMC9230049.

- AlQuaiz A et al. Int J Womens Health. 2022 Dec 16;14:1709-1722. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S387259. PMID: 36561605; PMCID: PMC9766474.

- Mitsuhashi R et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Dec 29;20(1):569. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20010569. PMID: 36612891; PMCID: PMC9819475.

- Mohebbi Dehnavi Z et al. BMC Womens Health. 2018 May 31;18(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0565-5. PMID: 29855308; PMCID: PMC5984430.

- Yesildere et al. Complement Ther Med. 2020 Jan;48:102272. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102272. Epub 2019 Nov 27. PMID: 31987230.

- Samadi Z et al. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2013 Jan;18(1):14-9. PMID: 23983722; PMCID: PMC3748549.

- Yaribeygi H et al. EXCLI J. 2022 Jan 24;21:317-334. doi: 10.17179/excli2021-4382. PMID: 35368460; PMCID: PMC8971350.

- De Souza MC et al. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000 Mar;9(2):131-9.

- Facchinetti F et al. Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Aug;78(2):177-81.

- Fathizadeh N et al. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2010 Dec; 15(Suppl1): 401–405.

- Ghanbari Z et al. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Jun;48(2):124-9

- Khajehei M et al. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2009 May;105(2):158-61.

- Bartram HP et al. Gastroenterology. 1993 Nov;105(5):1317-22.

- Gaffney BT et al. Life Sci. 2001 Dec 14;70(4):431-42

- Kalman DS et al. Nutr J. 2008 Apr 21;7:11.

- Berger D et al. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2000 Nov;264(3):150-3

- Kimura K et al. Biol Psychol. 2007 Jan;74(1):39-45.

- Timmcke JQ et al. FASEB J. 2008. 22; 760.